Published

The Sweet Science Behind Ice Cream

Ice cream, the beloved frozen treat enjoyed by millions worldwide, is not merely a simple mixture of cream and sugar. It’s easy to overlook the work and science that goes into crafting this frozen treat. Ice cream may seem simple, but it’s more than just frozen milk fat. Ice cream, to put it simply, is a delicate dance of ingredients and processes, orchestrated by the principles of culinary science.

We may not have put a lot of thought into the science behind ice cream when we were kids, chasing after that ice cream truck, but there is a ton of stuff that happens behind the sciences. Have you noticed how some ice cream may be thick and creamy, and others may be fluffy and light? Have you noticed how some ice cream just feels colder on the tongue, and others may not be as frosty? Have you noticed how some ice cream just seems so easy to scoop into perfect balls (or quenelles, if you’re fancy), and others are hard as rock after a long time in the freezer?

In this exploration, we’ll delve into the molecular marvels and culinary craftsmanship that makes the ice cream experience so varied and different. But at the end of it all, we’ll all come to agreement on one thing - ice cream is just so irresistibly delicious.

A Chilling History

This isn’t a regular history lesson - we’ll be looking at the historical discovery that made the existence of ice cream possible.

Iced drinks and desserts have been around for a long time. In ancient Greece, street merchants would sell snow, often used to cool down wine on hot days. Roman emperor Nero reportedly had a taste for iced milk seasoned with fruits and honey.

What really enabled the makings of modern day ice cream, however, goes back to the thirteenth century. Arabs at the time made the discovery that ice mixed with salt set in motion an exothermic chemical reaction, which created a heat-sucking mix with a far lower freezing point than typical water. Immersed in this bath of super powered brine, various concoctions of milk and sugar were able to easily form ice crystals. When stirred and shaken regularly, a scoop-able frozen foam would form, as the motion would prevent large ice crystals from forming. Hence, the basis for good, delicious ice cream would form.

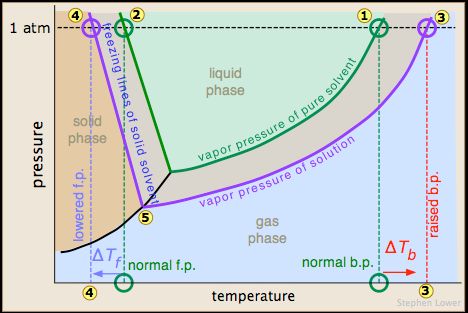

Remember this principle - when you add sugar or salt to liquids, the freezing point of the concoction drops. Basically, any non-volatile solute (like salt) dissolved in a solvent (like water) lowers the vapor pressure of the solvent. The vapor pressure of the water is lowered whenever a solute is added to a solvent because there are fewer solvent particles on the surface to evaporate. This lower vapor pressure equates to a lower freezing point, as seen in Temperature vs Atmospheric Pressure graph below:

This drop in freezing point not only creates the environment necessary for making ice cream, but it also allows ice cream to form in said environment. When you freeze cream, the cream on its own becomes rock hard. Add sugar to soften and sweeten it, and you lower the freezing point. That means it won’t get cold enough to freeze when you put it in solid ice, because the freezing point of water is higher than that of sweetened cream. The ideal modern ice cream follows this aforementioned principle - put the sweetened cream in an environment surrounded by salted ice, and quickly churn it to develop tiny ice crystals. Hence, the pursuit for perect ice cream was born.

The Chemistry Behind Creamy Goodness

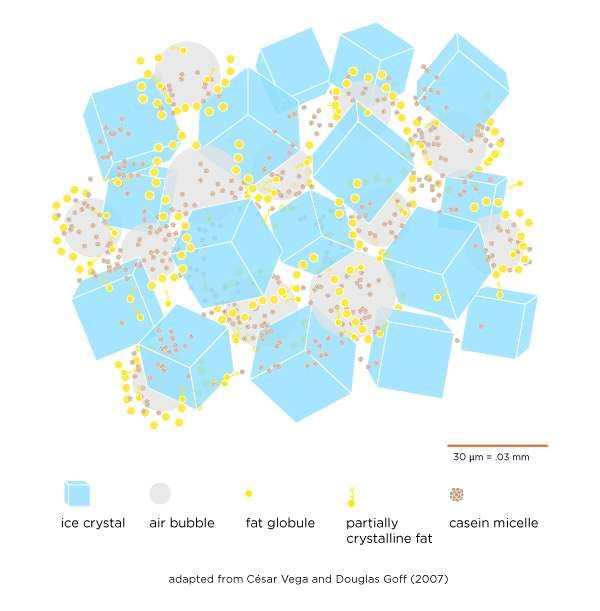

Contrary to what its name may imply, ice cream is more than just frozen cream. At its core, ice cream is a symphony of ice crystals, concentrated sweetened cream (made of liquid water, milk fat globules, milk proteins, and sugar), and air that comes together to form a soft, creamy mixture that melts quickly and naturally under the heat of our mouths:

The ice crystals form from water molecules as the ice cream mix freezes. The size of the crystals determines whether the ice cream is fine and smooth or coarse and grainy, and it also determines the temperature you perceive as it hits your tongue: grainy ice cream will feel colder than a more smooth-textured mixture. (This difference in temperature is because larger ice crystals require more heat to melt. Since this takes heat away from your mouth, it makes the ice cream seem colder.) Though ice crystals account for much of the ice cream’s solidity, they make up only a fraction of its volume.

The concentrated sweetened cream is what is left of the mix when ice crystals form. Thanks to all the dissolved sugar, about a fifth of the water in the mix remains unfrozen even at 0 °F / -18 °C. The result is a very thick fluid made of about equal portions of liquid water, milk fat globules (both liquid and semicrystalline), milk proteins (casein micelles and whey), and sugar. This fluid coats each of the many millions of ice crystals and sticks them together. When you churn the ice cream, the semicrystallized globules of milk fat knock together and form long, pearl-like strands that wrap around the air bubbles, yielding a stable foam and giving ice cream most of its volume.

Air cells are trapped in the ice cream mix when it’s churned. They interrupt and weaken the matrix of ice crystals and cream, making that matrix lighter and easier to scoop and giving your ice cream a melty, luscious mouthfeel. The air cells also inflate the volume of the original mix. The increase is called overrun, and in a fluffy ice cream, it can be as much as 100 percent: that is, the final ice cream volume is half mix and half air. The lower the overrun, the denser the ice cream.

What Makes For a Good Pint?

Now that we know the science, we can really delve into the characteristics of a good pint of ice cream. Ice cream always tastes good, but what do ice cream connoisseurs really look for when they’re hunting for a legendary scoop?

Let’s look into the ice crystals first. The size of the ice crystals that form during churning is super important to the texture, mouthfeel, and flavor intensity of the ice cream. Small ice crystals will make the ice cream smoother, more flavorful, and less cold when it hits your tongue. Large ice crystals will give the ice cream a coarse texture, suppress the flavors and aromas of added flavorings, and provide an undesirable, icy mouth-feel. Good ice cream ideally should be smooth and flavorful, with no large ice crystals that grate against your tongue.

Now, it comes to the sweet cream. Adding more fat in the form of cream will make your ice cream richer. Add too much fat, and it will have a slick mouthfeel and can harden completely in your freezer. High fat slows flavor release, making for a long, lingering flavor, while lean ice cream has a crisp, bursting flavor that doesn’t linger as long. In contrast, milk will make your ice cream icier and harder because milk is made up mostly of water, which will freeze into ice crystals. In moderation, milk is very important to the molecular makeup of your frozen treat and helps to reduce the richness added by cream. Adding more sugar will improve flavor (to a point) and soften the final product. Add too much, and your ice cream could be cloying or runny, or it won’t freeze at all. At the end of it all, good ice cream should have a nice balance of cream, milk, and sugar - have enough fat to provide a luxurious mouthfeel, enough milk to cut down the richness, and enough sugar to soften the ice cream but not to the point that it runs off your spoon.

Finally, the air - this gives ice cream its softness, making it pliable and easy to scoop. We often see that “premium” ice creams (selling somewhere between $8 - $15 per pint at the store) tend to have lower overrun with around 25% of air added during churning, while cheap ice creams can have as much as 100% overrun. This makes sense, since adding air to the cream mixture is an easy way to increase the final volume of ice cream without increasing the manufacturing cost. However, this begs the question: is lower overrun objectively better for ice cream? I’d say it comes down to personal preference - some people prefer a dense, creamy ice cream with low overrun, and some people prefer a light, fluffy ice cream with high overrun. Personally, I really like a good balance (around 50% overrun), to make my treat a luxurious, creamy delight while keeping things light.

The Final Scoop

Now that we know the science behind ice cream, we can all become qualified to judge our local ice cream shops, leaving behind Yelp reviews and dropping knowledge all over the place. Hooray! Whenever I talk about a new ice cream place on a post, I won’t be going into as much detail on the overrun and ice crystal sizes as I have here. However, having this knowledge on the back of our heads will help us objectively determine whether or not an ice cream place truly meets our demanding palates.

At the end of it all, I really want to emphasize that ice cream is not just a frozen dessert; it’s a testament to the wonders of culinary science and human ingenuity. From its humble origins to its modern incarnations, ice cream continues to captivate our taste buds and inspire culinary innovation.

So the next time you indulge in a scoop of your favorite flavor, take a moment to appreciate the scientific marvel that lies beneath its frozen facade. For in every lick and every swirl, there’s a world of chemistry and craftsmanship waiting to be savored.